Next week, the Hall of Fame class of 2018 will be announced. As usual, the last several months have included tremendous hemming and hawing over the ballot and its abundance of, or lack thereof, worthy candidates. Jon Heyman lamented his “bad ballot”, Joe Posnanski examined every member of the ballot, and Ryan Thibodaux tracked every available ballot. Every year, fans and writers, argue for two months over which players belong in the Hall of Fame, whether or not to disqualify players for accused cheating or for their personalities, and, in the end, only a couple of players join the pantheon of immortals enshrined in Cooperstown. As Bill James documented in Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame, we spin the same poorly formed arguments every year:

Quotes wrenched out of context to prove something they were never meant to prove, statistics flung like Molotov Cocktails at the old order…

Plenty of new insightful pieces have been written about the Hall of Fame over the last several months. Last week, on ESPN.com, Bradford Doolittle dug deep to find how every player on the current Hall of Fame Ballot compares to enshrined Hall of Fame players at the same position according to “JAWS,” the Jaffe WAR Score System. At the Ringer, Zach Cram explained why the pace of Hall of Fame growth remains consistent, even if it feels sluggish. At FanGraphs, Craig Edwards took voters to task for the Hall of Fame “mess” they led to by creating a logjam of worthy players. Unfortunately, the backlog of players who belong in the Hall of Fame is not new, nor is the idea of trying to find objective truths to quantify the Hall of Fame. More importantly, none of these pieces address the issue that the Hall is simultaneously too small and too large.

In a 2011 piece for the NY Times, Nate Silver documented that 13 percent of players reached the Hall of Fame during parts of the ’20s and ’30s. Standards for those players were complicated by the Veteran’s Committee which, under the influence of Frankie Frisch, elected seven of Frisch’s teammates. Many of these former teammates would have a hard time making the Hall of Fame under modern standards, such as Jim Bottomley and High Pockets Kelly. Since these players were first basemen, let’s look at the position as a case study and go ahead and see how they compare to their hallmates. We can also throw in Frank Chance, whose case as a player was rather shaky. (Scroll to see entire stat line.)

OPS+ is a median while all others are cumulative averages.

In defense of Frank Chance, he almost certainly belongs in the Hall as manager, after leading the early 1900s Cubs to four pennants and two World Series titles, totaling a .664 winning percentage as player/manager.

Turning our attention to the first basemen on the 2018 ballot, it appears that Jim Thome could make the Hall in his first ballot, while momentum is also building for Edgar Martinez. We also still have holdouts making the case to vote in Fred McGriff, in his penultimate year on the ballot.

Unfortunately, McGriff falls well below the median OPS+ for the 17 first basemen in the our modified Hall of Fame and his cumulative and peak WAR totals are rather anemic compared to the enshrined players. He beat the home run average but he also played in one of the most extreme offensive eras in MLB history. He also stole fewer bases than the average Hall of Famer (while getting caught more often). It looks like the case for McGriff isn’t great. That outlook doesn’t get better when you compare McGriff to some of his peers who overlapped his career:

These guys were good.

I left the players above in a random order because they all accumulated very solid careers and I would not want to skew your assessment of this group. We can make cases for any of these players to be enshrined in the Hall of Fame, but Thome, McGwire, Martinez, and the still-active Cabrera certainly lead the pack. Hernandez trails in OPS+ and other offensive categories, but he may have been the greatest defensive first baseman of all-time at the time of his retirement. Fans and writers bemoaning the surge in support for McGriff point out that, if he belongs in the Hall, then so does Will Clark. The other players on this list meet or exceed Hall of Fame standards for WAR, OPS+, home runs, and other categories. I wanted to include first basemen from other eras but every first baseman who debuted before Hernandez, and scored higher by JAWS, is already in the Hall of Fame.

This is because, as Silver pointed out in his piece, a lot more players used to make the Hall of Fame. As more writers got to voice their opinions and as more players became active, the rate of players making the Hall of Fame dropped precipitously. This pack will only become more difficult in future seasons as Todd Helton, Lance Berkman, Jason Giambi, David Ortiz, Mark Teixeira, Albert Pujols, Joey Votto, and others with Hall of Fame credentials enter the ballot.

If there are too many players and not enough room on the ballot, or if the lack of clarity as to who should go to the Hall prevents writers from making the correct votes, should we simply ignore the Hall of Fame? Is it, as FanGraphs author Paul Sydan put it, “not worth our time?”

I have another idea, and it’s the one small trick that will help us all relax and enjoy baseball without the stress of the annual Hall of Fame brawl: make your own Hall of Fame.

You, as a devoted baseball fan, have all of the tools and resources available to you that many BBWAA members use to form their Hall of Fame ballots. What is your vision for the Hall of Fame and who exemplifies the qualities that you envision make them worthy of immortality?

Adam Darowski and company did this very thing with the Hall of Stats. The Hall of Stats set the Hall of Fame limit at 222 players, the number of players on the real Hall of Fame roster at the time the site was founded, kicked everyone out and then reformed the Hall of Fame around a formula that ranks every player in baseball history.

Maybe you do not have time to make your own formula, but you would like an idea of where to start. I have a suggestion for that approach, as well, as I previously compiled a list of metrics to determine Hall of Fame worthiness.

If you want to look beyond stats and find out what people who watched candidates closely think of their case, you could seek out local writers and find out how they are building the case for players they watched during their career. Veteran Braves reporter Mark Bowman built a case for Fred McGriff based not only on stats but on the recommendations of Hall of Fame manager Bobby Cox, Hall of Fame pitcher John Smoltz, and former MVP Terry Pendleton. While abstaining from voting for all but two players makes Bill Livingston’s ballot feel like an affront to the sacred privilege of voting for the Hall of Fame, you can glean his feelings about Omar Vizquel and Jim Thome and add that information to your decision.

My plea for your Hall of Fame is that you find a consistent vision and stick to it. Imagine the Hall of Fame as you see it and then fill it with the players who fit that vision. With nearly the entire history of baseball at your fingertips, you can find plenty of resources online to help you in your quest. Baseball-Reference.com provides plenty of Hall of Fame resources. You can simply set a FanGraphs leaderboard to include all players at a position and then sort by batting or fielding stats.

If you want to build a Hall of Fame that includes room for the greatest defenders at their positions, in addition to heavy hitters, then you could check Baseball-Reference.com’s career dWAR leaderboard. If you want to include a player like Omar Vizquel, should you also consider Mark Belanger, Bob Boone or Jim Sundberg? Maybe you want to make sure that the all-time on-base kings have a place in your Hall, so you will need to consider Riggs Stephenson, Max Bishop and, one of the greatest two-way players of the modern era, Lefty O’Doul.

As a fan of baseball analytics, my Hall of Fame would build on players whose statistical performances placed them in the upper echelon of baseball’s great players. I could not imagine a Hall of Fame without Barry Bonds or Roger Clemens. The older I get, however, the more I realize that the chance to remember and watch players who made an impact in their prime is a privilege I would like future baseball fans to enjoy. Why wouldn’t I want to remember a player like Dale Murphy, who was the greatest homegrown Braves hitter between Hank Aaron and Chipper Jones and who spent several consecutive years as one of the best players in baseball?

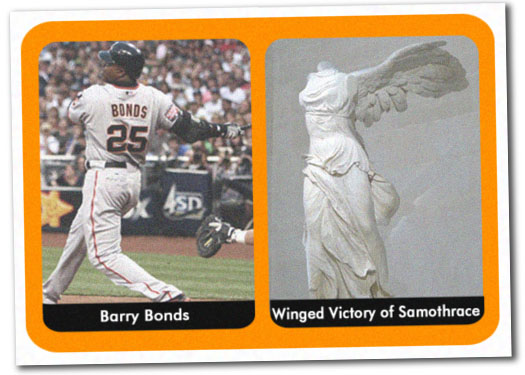

Maybe my Hall of Fame would look more like the Louvre than a Hall of Stats. In the Louvre, no one should look at the Venus de Milo and ask if it is better or worse than The Winged Nike. They are both cultural icons that should be preserved. In place of art collections organized by period medium, my My Hall of Fame collections could be organized by the greatest defenders, greatest hitters, greatest power pitchers, and so on. It could include the players who were cultural icons to their team, even in eras of futility, like Murphy on the 1980s Braves or Ryne Sandberg and Andre Dawson on the late ’80s Cubs. Like works in the Louvre, I would like to preserve the cultural icons from baseball history for future generations.

Whatever you do, just make sure there’s a place for Kenny Lofton and Bill Dahlen in your Hall of Fame. Maybe one day, electors will correct these egregious errors. Until then, we will have to fix some things for them.

Next post: The Current State of Intentional WalksPrevious post: Hall Worthy: You Decide?

Leave a Reply