Although the 2015 season is still months away, it doesn’t hurt to look ahead, or in a sense look back. In this instance, I wanted to throw some red flags on players who may have been fortunate in 2014.

I have talked about BABIP in the past and its ability to act as an underlying tool to understand batting averages. In the Fantasy Baseball world, batting averages not only represent one hitting stat, but they help model runs, RBI, and in rarer cases, even stolen bases. Being fortunate on the number of balls you put in play that go for hits clearly helps you put up more runs. Players will be on base more often, leading to more opportunities to score runs and even steal bases. In the real baseball world, BABIPs engineer your overall offensive performance, as your entire slash line can shoot up, and consequently, your overall WAR value.

A quick refresher on BABIP

High BABIPs can be the result of several factors. Generally, fast players spur high BABIPs as they can beat out ground balls or even reach base through bunting. Jose Altuve did play slightly over his head in 2014, but his lightning-quick foot speed enables higher batting averages on those bunts and ground balls. For that reason alone, we cannot throw out a batting title season as a fluke. Similarly, Michael Bourn’s .342 career BABIP can be primarily attributed to his foot speed.

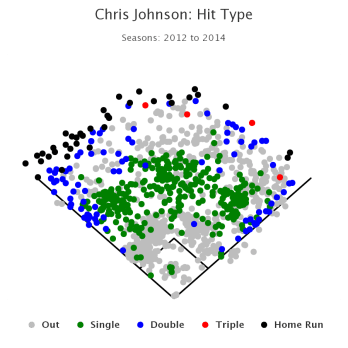

On the other hand, take a player like Chris Johnson. He is 6’3 and 225 pounds, with 16 stolen bases total since 2009. While he is arguably quicker than the Molina family, he does not move very quickly out of the batter’s box, nor does he bunt for hits (career total of 0 bunt hits). Johnson has a line drive swing with hardly any uppercut at all. As evidenced by a consistently above-average line drive rate (career 25.3%), he is constantly hitting balls with a low trajectory, an approach that leads to more hits. As seen in his spray chart, he deposits balls all over the field. His teammate Freddie Freeman has that same ability.

A by-product of the line drive swing, the knack of eliminating pop-ups drives up BABIP as well. Simply with regard to plate appearance outcomes, a pop-up is essentially a strikeout that counts as a ball in play. Like high strikeout hitters struggling at maintaining high batting averages, high pop-up players like Jose Bautista (career .271 BABIP) and Andrelton Simmons (career .262 BABIP) rarely generate high BABIPs.

Not surprisingly, the best hitters can do all of these things. Mike Trout’s career .361 BABIP is supported by his speed, line drive-generating swing and not many pop-ups. With the principal driver being the line drive stroke as opposed to the speed, pure hitters like Miguel Cabrera and Joe Mauer can keep their rates high without the foot speed. They also have the coveted ability to hit to all fields. With these keys in place, we can ask the question of which players lacking these skills recorded high BABIPs in 2014. In other words, who benefited from good fortune in the BABIP department, and subsequently in their batting line?

Casey McGehee

McGehee hit .287 last year, which does not look outlandish at first glance. For some, their eyes immediately turn to a career best .335 BABIP. McGehee posted an 18.2% line drive rate that was roughly 3 percentage points below average. While he did generate an abundant amount of ground balls, he was statistically one of the worst baserunners and to the naked eye he is clearly sub-par on the basepaths. Truthfully, he has some Chris Johnson to his swing, though the foregoing caveats are sufficient to rule him out as an above-average BABIP guy. When his sub-.300 career BABIP is factored in, a .287 batting average is definitely a reach, even if his improved plate discipline is legitimate.

Josh Harrison

Harrison had a wonderful season in 2014, playing all over the diamond for the Pirates in addition to an .837 OPS. The question is whether his .353 BABIP can be sustained. He is an interesting case in this analysis as he possesses some of the tools discussed, including good foot speed and limited pop-ups. In fact, he also had a 24% line drive rate. My scepticism stems from that career-high line drive rate, along with a pull-hitting approach, visible in his spray chart. His .355 BABIP generated a .315 average, and the smart money would be on knocking at least 30 points off both those numbers. Fortunately for Harrison, his 2014 BABIP helped him to land a starting job, likely making him safe from the super-utility fate he was doomed for a year ago.

Michael Brantley

Brantley also aligns with the other regression candidates. His career year, which included a 155 wRC+ (5th in the AL) leaves a lot to be bearish on. He has respectable speed, and a unique ability to never whiff on pitches. This control of the strike zone allows him to see better pitches, as pitcher’s have trouble making him chase and as a result, strike out. Congruently, he also rarely pops up the ball on the infield. He rocked a .333 BABIP last season, primarily driven by a 25.7% line drive rate, consistent with the likes of Chris Johnson and Joe Mauer. Is this rate sustainable? He has improved the rate each of the last 3 years, though batted ball rates like this don’t necessarily increase linearly very often. Brantley did not have a qualified BABIP above .310 before this year, despite checking off next to all of the high BABIP boxes.

In many cases, hard-hit rates (measuring harder versus softer hit balls) may add insight, especially to Brantley, as while he may have been generating good batted ball angles, he may have been making weaker contact (in terms of velocity off the bat) than other players with this profile before this year. In 2014, both he and Harrison were near the top in that department, but with both not operating high BABIPs in prior years, I would assume we just saw a peak year. For Brantley, it is more likely an overall improvement at the plate, so we would be regressing only some of that BABIP-driven average.

As mentioned with Brantley, the quality of contact would more clearly be measured with Hit FX, or in the medium term, StatCast, both of which are unavailable to the university student. Nevertheless, with the information the public does have access to, we can certainly measure most cases of batted ball luck versus skill, and the degree to which each played a part in a hitter’s season . Whether it is foot speed, batted ball profiles or spray charts, I would encourage all to isolate their own cases of regression or progression.

Next post: A Festive Post – Naughty & Nice PitchersPrevious post: You’re an All-Star. Get. Paid.

Leave a Reply